Charles Andrew Cross is asked to give evidence as a witness to the murder of Mary Ann Nichols to Mr. Wynne E. Baxter, Coroner for South-East Middlesex, at the Working Lad’s Institute on the Whitechapel Road on the Monday after the murder (3 September 1888). On reporting his testimony the Times and the Morning Advertiser newspapers report his name as ‘George’ and ‘Charles Allen’ respectively, while the coroner’s recorder names him as ‘Charles Andrew.’ These discrepancies need not over worry us at this point. As a member of the lower social order’s (a carter by profession) the exact details of his name were not likely to have been greatly important to newspaper reporters more interested in the print value of the more gruesome details of a murder story. What is important is that they all concur that he gave his name as ‘Cross.’ It is intriguing that of the five civilian witnesses who gave evidence at the coroner’s court that day he alone did not provide his home address, offering rather the carriers Messrs. Pickford and Co. as his place of employment. Neither the court nor the newspapers appear to pick up on this evasion. As to why his address is accepted now as 22 Doveton Street, Mile End will have to wait for another discussion.

Accepting, for the moment, that his home address was 22 Doveton Street – as it was reported in the Morning Advertiser that he crossed Brady Street to enter Buck’s Row he certainly was coming from that direction – we do find a ‘Charles A.’ living at that address less than three years later in the 1891 census, but this is a Charles A. Lechmere. This man is a forty-one year old carman, who was born in Soho, and living with his wife Elizabeth and their seven children. This man, Charles A. Lechmere, was born at St. Ann’s in Soho in 1849 and was one year old at the time of the 1851 census. After the death of his father, John Allen Lechmere, his mother, Maria Louisa Roulson, remarried in 1858 a police constable by the name of Thomas Cross. By the time of the 1861 census the family are living at 13 Thomas Street, St. George East and the eleven year old Charles has taken the name Cross. At twenty-one (census of 1871) he has married Elizabeth, is employed as a carman and has reverted to the name Charles A. Lechmere. In the census of 1881 we find him named Charles Allen Lechmere, and still working as a carrier. Charles Allen Lechmere would have been thirty-nine in 1888 and would have been employed as a carman for about twenty years – as stated by Charles A. Cross at the Nichols’ inquest. His stepfather, Thomas Cross, appears to have died at St. George East in 1869 and at no point after this does Charles use the name Cross again for official records, save at the Nichol’s inquest.

We are left with two pressing questions which merit further examination: why was Lechmere not forthcoming with his full address, and why did he feel the need to use an alias at a murder inquest? Considering that he was alone when he discovered the body of Mary Ann Nichols, that he was alone with her for between ten and twenty minutes without raising an alarm, and that he left the scene of the crime, he is a figure who demands further investigation.

When PC John Thain (96J, Bethnal Green) arrived back at the scene of the crime on Buck’s Row with Dr. Llewellyn at about between ten minutes to and four o’clock in the morning, the doctor conducted a cursory preliminary examination of the body. The legs of the dead woman were extended, and there were severe injuries to her neck. In the dark he felt that her hands and wrists were cold, but that her torso and lower extremities were warm. Llewellyn estimated that she had not been dead more than thirty minutes. This places the time of death to between twenty and ten to four in the morning. At the scene he noted that there was little blood to be seen about the neck which had led some to believe that she may have been killed somewhere else and brought to the place where she was discovered.

When PC John Thain (96J, Bethnal Green) arrived back at the scene of the crime on Buck’s Row with Dr. Llewellyn at about between ten minutes to and four o’clock in the morning, the doctor conducted a cursory preliminary examination of the body. The legs of the dead woman were extended, and there were severe injuries to her neck. In the dark he felt that her hands and wrists were cold, but that her torso and lower extremities were warm. Llewellyn estimated that she had not been dead more than thirty minutes. This places the time of death to between twenty and ten to four in the morning. At the scene he noted that there was little blood to be seen about the neck which had led some to believe that she may have been killed somewhere else and brought to the place where she was discovered.

On hearing the news of the murder a couple of women came forward and it was discovered that someone answering to the dead woman’s description, known only as “Polly,” had been staying at a common lodging-house at 18 Thrawl Street in Spitalfields. Women from the house were brought to the morgue whereupon they identified her as the “Polly” with whom they shared a 4d room, each having their own bed. “Polly” had been turned away from the lodging-house on the Thursday night because she did not have the 4d nighty price on her. “I’ll soon get my ‘doss’ money,” she was heard to have said, “See what a jolly bonnet I’ve got now.” She was wearing a new bonnet. “Polly” was last seen at half past two on Friday morning on the Whitechapel Road, opposite the church at the corner of Osborn Street. An inmate of the Lambeth Workhouse, Mary Ann Monk, was brought to the mortuary, and after twice viewing the body was convinced that it was that of Mary Ann Nichols, also known to her as “Polly” Nichols.

On hearing the news of the murder a couple of women came forward and it was discovered that someone answering to the dead woman’s description, known only as “Polly,” had been staying at a common lodging-house at 18 Thrawl Street in Spitalfields. Women from the house were brought to the morgue whereupon they identified her as the “Polly” with whom they shared a 4d room, each having their own bed. “Polly” had been turned away from the lodging-house on the Thursday night because she did not have the 4d nighty price on her. “I’ll soon get my ‘doss’ money,” she was heard to have said, “See what a jolly bonnet I’ve got now.” She was wearing a new bonnet. “Polly” was last seen at half past two on Friday morning on the Whitechapel Road, opposite the church at the corner of Osborn Street. An inmate of the Lambeth Workhouse, Mary Ann Monk, was brought to the mortuary, and after twice viewing the body was convinced that it was that of Mary Ann Nichols, also known to her as “Polly” Nichols.

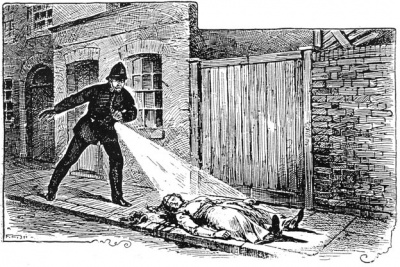

He saw that the woman was lying on her back and that her bonnet was on the ground close to her left hand. Blood was still oozing from a wound on her throat, but her arms, from the joints upwards, were still quite warm. He saw PC John Thain (96J, Bethnal Green) passing along Brady Street to the east and signalled him with his torch so as not to raise an alarm at about a quarter to four in the morning. Neil then directed Thain to get Dr. Rees Ralph Llewellyn who lived nearby. Very shortly after this PC Jonas Mizen (56H, Whitechapel) arrived on the scene and was dispatched by PC Neil for an ambulance. According to Mizen (Inquest testimony, Monday 3 September 1888) Charles Cross and Robert Paul met him and informed him that another officer was looking for him. Cross denied this in his own testimony. Thain returned with the doctor at about ten minutes to four in the morning.

He saw that the woman was lying on her back and that her bonnet was on the ground close to her left hand. Blood was still oozing from a wound on her throat, but her arms, from the joints upwards, were still quite warm. He saw PC John Thain (96J, Bethnal Green) passing along Brady Street to the east and signalled him with his torch so as not to raise an alarm at about a quarter to four in the morning. Neil then directed Thain to get Dr. Rees Ralph Llewellyn who lived nearby. Very shortly after this PC Jonas Mizen (56H, Whitechapel) arrived on the scene and was dispatched by PC Neil for an ambulance. According to Mizen (Inquest testimony, Monday 3 September 1888) Charles Cross and Robert Paul met him and informed him that another officer was looking for him. Cross denied this in his own testimony. Thain returned with the doctor at about ten minutes to four in the morning.